Most of the tools you’ll be using in the terminal, including those presented in the previous chapter, were designed by the people who created UNIX back in the late sixties and early seventies. They did an amazing job. People like Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie are heroes in the computing world: the system they created is at the heart of most servers running the internet, and at the core of all macOS and Linux computers. Dennis also invented the C programming language, with which most of the rest has been written.

The tools you’ll be running are not the ones they wrote; there have been plenty of rewrites over the years. Yours most likely come from the GNU project, the brainchild of Richard Stallman —another legendary programmer— or from the BSD UNIX from Berkeley. When looking at the man page of any program type G to go to the end, and you’ll usually see something about the history of the program and its authors there.

Let’s get started. Open the terminal and go to the changek directory that you built in the previous chapter. And check out what’s in there, just in case.

cd ~/changek ; ls

index.html

(Note how we can have more than one command per line if we use a ; to separate them.)

Just as we left it in the previous chapter. We can also see what’s in index.html,

cat index.html

Hi there

How's that going?

Downloading files from the web

The two main command-line programs to download from the web are curl and wget. Most likely you’ll have curl installed if you are on macOS, and wget if you are on Linux. Both work similarly.

Let’s practice by downloading a sample data file. We don’t want to litter our working directory with downloads, so let’s first build a temporary directory:

mkdir ~/tmp

and move to it:

cd ~/tmp

Now let’s download a sample CSV file:

curl -LOs https://raw.githubusercontent.com/datasets/population/master/data/population.csv

The options mean:

-Lfollows redirects-Osaves with the original filename-ssilent mode

And make sure it came:

ls -lh population.csv

-rw-r--r-- 1 user staff 1.2M Jan 15 10:00 population.csv

You can peek at the contents:

head population.csv

Country Name,Country Code,Year,Value

Arab World,ARB,1960,92490932

Caribbean small states,CSS,1960,4190810

Central Europe and the Baltics,CEB,1960,91401874

East Asia & Pacific (all income levels),EAS,1960,1042550110

East Asia & Pacific (developing only),EAP,1960,896708266

Euro area,EMU,1960,260385009

Europe & Central Asia (all income levels),ECS,1960,667039992

Europe & Central Asia (developing only),ECA,1960,168260282

European Union,EUU,1960,406749670

Bundling files with tar

The tar program bundles many files into one, usually named with the prefix tar, and extracts files from a tar bundle.

Files can be compressed in various formats. The .tar.gz or .tgz extension indicates a tar archive that has been compressed with gzip. The .zip format is another common compression format. Let’s create a tar archive example:

echo "example content" > example.txt

tar czf example.tar.gz example.txt

You should always check the contents of a tar file before unpacking it. You do it with the tvf options, as in

tar tzf example.tar.gz

-rw-r--r-- 0 user staff 16 Jan 15 10:00 example.txt

(Note how I piped the output of tar to head, a program that shows the first lines of the input and ignores the rest, so I didn’t have to clutter the page too much.)

The content of the tar file looks good, so let’s unpack it. Replacing the t in the options with an x,

tar xzf example.tar.gz

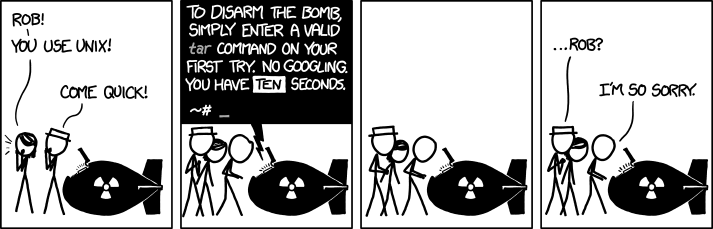

(which makes me think of the classic xkcd joke:)

For zip files, you would use the unzip command:

unzip example.zip

Creating tar files

You’ll certainly want to build tar files. You do it by replacing the x in the options by a c, and by specifying a file name for the bundle. We could, for example, pack the content of our working directory with:

cd ~ ; tar zcvf changek.tgz changek

a changek

a changek/index.html

Summary of tar

The tar program has many more options and interesting use cases, but basic usage is not so bad. You can certainly remember the three main incantations:

- Create a file bundle with

zcvf,

- Check the contents of a bundle with

ztvf

- And unpack a bundle with

zxvf,

Move things in place

After unpacking an archive, you typically want to move the extracted files to their final location:

mv ~/tmp/extracted-files ~/changek/data ; cd ~/changek ; ls

data index.html

Finding files with find

This is another tool that you’ll probably find yourself using all the time. The basic invocation is:

find . -name "*.txt"

The first argument is the directory where you want to search. The -name is the search condition. You can use wildcards in your searches. For example, to find all Python files:

find . -name "*.py"

./scripts/setup.py

./scripts/test.py

When using wildcards with find, it’s safer to quote them:

find . -name "*.py" # Good - quotes protect the wildcard

find . -name *.py # Bad - shell might expand this

Without quotes, the shell might expand *.py to actual filenames in the current directory before find sees it

which is not what we wanted.

We can call find with all sorts of interesting arguments. For example, if we want to limit the search to files we can say

find . -name "*.txt" -type f

Or we can find the files that have been modified in the last minute,

find . -name "*.txt" -type f -mtime -1m

We get nothing, because none of the files has been modified in the last minute. Let’s force it by using touch on one of the files. With touch you set the file’s access time to now (and you create the file if it didn’t exist):

touch ./example.txt

And now search again,

find . -name "*.txt" -type f -mtime -1m

./example.txt

Looking for differences between files

The diff program returns the difference between two files, using a clever but easy to understand syntax. Let’s take two identical files: the index.html file, and an exact copy:

cp index.html another.html ; ls

another.html data index.html

Let’s run diff on them:

diff index.html another.html

Nothing. Good. When two files are identical there is no difference. Remember what was on index.html,

cat index.html

Hi there

How's that going?

Let’s append another line in another.html,

echo "Yet another line" >> another.html

and another one, just for fun,

echo "This is the last line" >> another.html

Now check the contents,

cat another.html

Hi there

How's that going?

Yet another line

This is the last line

Nice. Let’s check again the output of diff,

diff index.html another.html

2a3,4

> Yet another line

> This is the last line

Here it is. It tells you that, after line 2, lines 3 to 4 have been added, and it lists the new lines. This is something that you’ll use all the time to answer questions like did I change this file? Is it the same as that other file?

Find text in files

The grep program can find text in files. For example, to extract from index.html the line that contains the word that you can do

grep that index.html

How's that going?

You can call it with several files, and it will tell you to which file the line or lines it found belong:

grep there *.html

another.html:Hi there

index.html:Hi there

If you want to match words ignoring differences between capital and non-capital letters you can use the -i option,

grep -i yet *.html

another.html:Yet another line

Finding words in files of a particular type

This is another problem that pops out very often. Say you want to find which among your Python files (ending in .py) include a particular word, and that your files are spread in several subdirectories. (We’ll learn more about Python in a later chapter.) Or, as we are going to do, which among your .html files contains the word there. Let’s first move one of the files to a directory,

mv another.html data ; ls

data index.html

The first thing we need to do is to find all the .html files, and we know how to do that:

find . -name \*.html

./data/another.html

./index.html

Now we would like to pipe this results to grep, but we have a problem: the output of find is just text; it happens to represent file names, but if we send it go grep as is grep will never know. It will think it is plain old text, and it will search for whatever we want to find within it. For example,

find . -name \*.html | grep another

./data/another.html

We’ve found the line that contains another, but we’ve done nothing to the contents of the files. This is useful when you want to find a file whose name contains a word, but now we want something else: we want to peek inside the files.

In order to do that we need another program: xargs, which is kind of tricky: it takes standard input and a program, and arranges things so that the standard input is sent as the files of that program. For example, lets send the name of a file to standard output, to be piped:

ls *.html

index.html

Now we pipe it to xargs, so that it goes to its standard input:

ls *.html | xargs grep -i hi

Hi there

Whatever xargs received in standard input (in this case, the output of ls) it sent as a parameter to the program grep -i hi.

Knowing this, we can refine our incantation so that it does search inside files, as

find . -name \*.html | xargs grep -i hi

./data/another.html:Hi there

./data/another.html:This is the last line

./index.html:Hi there

Do you see why it found two lines in ./data/another.html? Remember that -i stands for ignore case.

It turns out there is another way of running a program on all the files found by find. I think it is messier, so I only use it in the one ocasion in which the above command is messed up: when your file names include spaces. You do it with the -exec argument to find, followed by the command, ended in \;. In the place where you want the file names you put {}:

find . -name \*.html -exec grep -i hi {} \;

Hi there

This is the last line

Hi there

This sort of works, but it does not print the file name where the line was found. This is because grep has been called once per file, every time a file was found, instead of one time with all the files as before. And when you call grep with only one file it assumes you know what file you sent, and it does not write it back. In this case we don’t know it, because it was find doing the calling, so we ask grep to output the file name as well with the -H option:

find . -name \*.html -exec grep -i -H hi {} \;

./data/another.html:Hi there

./data/another.html:This is the last line

./index.html:Hi there

Much better. Another thing to know is that you can usually group arguments. In this case, the -i -H can become -iH, and it should still work:

find . -name \*.html -exec grep -iH hi {} \;

./data/another.html:Hi there

./data/another.html:This is the last line

./index.html:Hi there

In fact, this is what we were doing when calling tar (remember the zcvf and zxvf?). But tar is special in that it lets you not put the - in its optional arguments.

Looking for help

This section might be a bit overwhelming. Don’t worry: you don’t have to remember it all. You know how to look for help, and you will develop an intuition that tells you “I am sure there’s a way to tell this program to behave like this”. For example, I didn’t remember about the -H argument to grep, but I knew it had to be there. So I checked in the man page, and there it is. The things that you use all the time —and this will include the find piped to xargs with grep— you will remember without problems.